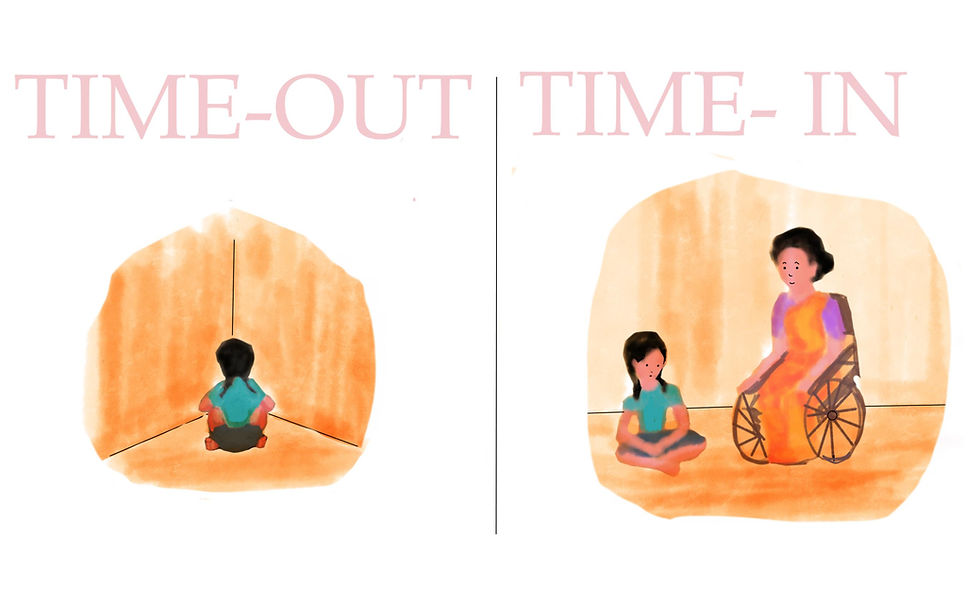

Choose Connection Through ‘Time-in’ Than Disconnection Through ‘Time-out’

- Growing Together

- May 7, 2020

- 6 min read

Time-out is a classic parenting strategy used by some parents to correct a child when the child misbehaves. The expectation of the parent using time-out is that the child spends a few minutes sitting alone and comes out of it calm and cooperative. This is how time-out works:

When a child behaves in a way that the parent finds disruptive, the child is asked to go to a pre-designated corner or chair or steps and asked to sit in silence/stillness

They are asked to reflect on what they had done in isolation (without any connection with their parents) for a specific period

They are accepted back to their regular environment when they apologize for their disruptive behavior

Though this process may work in the short-term, it may make the child feel disconnected from their parents, abandoned, humiliated, and sometimes even confused. Over a period, it may even lead to power struggles, resentment and yet you may feel that the problem that you want to address persists. As Pam Leo the author of the book Connection Parenting says :

“You can’t teach children to behave better by making them feel worse. When children feel better, they behave better”

An alternative and an effective & gentler approach to time-out is time-in. In a time-in approach, when the parent notices a child behave in a way that’s either bad for the child or causing trouble in the environment, instead of isolating the child and asking them to process it on their own, they support the child to process it in their presence while maintaining connection. This is how time-in works:

The parent approaches the situation with the mindset that the child is having a problem rather than thinking that the child is the problem

They physically move to a quieter place (along with the child) to work this out

They find out what is going on in the child’s mind, understand their needs and acknowledge it

They state their expectations from the child (taking the child’s needs into account) and share information if the child needs clarity

They stay with the child while the child processes the situation fully and take the next steps

As you can see, throughout the time-in process, the parent maintains a connection with the child by supporting the child while they process what had happened. The child learns emotional regulation in the supportive presence of a parent. They also learn a calm and connected way to react to situations as they observe the parent as a role model.

Let’s look at some examples of how these two approaches work.

Example 1

For instance, 4-year-old Nimish takes a handful of wheat flour and throws it on the ground and spreads it while the father is in the middle of another work. The father asks him to stop multiple times, but he continues to take more flour and drops it on the floor.

Time-out approach:

Parent: “Nimish, I told you not to play with the flour. Look at the mess you have made! Go to time-out for 5 minutes.”

When the child returns to the father after 5 mins, he asks him to not repeat this behavior.

(This approach may even leave the child perplexed and confused. The child might wonder why he is getting punished for simply having fun.)

Time-in approach:

1. Remind yourself that the child’s intention was to play and not to cause a mess

2. Physically move the child away from the flour and take him to a quieter corner (in case there are other distractions)

(Let’s assume the underlying need for the child in this instance was to have fun)

3. Acknowledge:

Parent: “Nimish, it looks like playing with the flour seems like a lot of fun to you, isn’t it?’

The child most likely would nod.

4. State Expectations:

Parent: “I want you to have a lot of fun. But today, all this flour has made a lot of mess, you see? When papa is on a call and asks you to stop something, I want you to stop it immediately. As soon as I become free, we can have fun together, ok?”

(When children feel acknowledged & don’t feel threatened, they have a lot of capacity to listen & they usually do)

5. Take the next steps:

Parent: “We need to clear this mess on the floor, Nimish. Could you please bring a wet cloth to clean it? Let’s clean this together. We can draw your favorite penguin with this flour before we start cleaning. Would you like that?”

The child would happily agree and even do an impeccable job of cleaning since his need for ‘fun’ is met.

(It is always a good idea to offer help to young children when they make amends. The child will do most of the work, but your presence & support will make a big difference to them.

Also, repeat the expectation you have from the child multiple times during the week so that the child can remember the instruction.)

Example 2

7-year-old Shirin pushes his 3-year-old brother Sahil sitting next to her. The parent asks her to stop but she pushes him again.

Time-out approach:

The parent tells Shirin that pushing is a bad habit. The parent sends Shirin to the time-out corner for 10 mins. Shirin is accepted back when she is ready to apologize.

While Shirin is in the time-out & tries to speak to the parent or get their attention, the parent ignores it. The child finally gives in and apologizes.

Time-in approach:

1. Remind yourself that the child is having a problem; the child is not the problem.

2. Physically move the 3-yr-old away to a safe place with another caretaker. Ask your 7-yr-old to join you for a discussion in a quiet corner.

3. Understand the child’s need

Parent: “Shirin, you are pushing Sahil again & again. It hurts him. I had to take him away from you. I know that you are a kind child, sweetie. I would like to understand, what’s going on with you?”

Shirin: “Sahil is always troubling me. He is very annoying. He takes all my toys”

Parent: “Sahil is taking all your toys, is he?”

Shirin: “Yes. You all always think he is cute & funny, but he is annoying. I don’t like him at all.”

Parent: “Looks like you are upset and annoyed”

Shirin: “Yes, you & papa are always with him, you don’t know how much he troubles me.”

Parent: “Hmmm, you want us to understand the troubles you are having and be more attentive to you, isn’t it?”

Shirin: “Yes” (continues to be sad)

(Let’s assume Shirin’s needs are understanding & closeness)

4. Acknowledge:

Parent: “Sweetie, you are right, we really need to spend more time together to understand what’s going on with you. I know I have been spending less time with you lately. Shall we go out for a mother-daughter brunch tomorrow?”

5. State Expectation:

Through the conversation, the parent found out that Shirin has been feeling lonely and needed her parents to understand what she is going through. This is a big emotion for a child to carry. Her behavior was a result of growing hurt and piled up emotions that she has been feeling for weeks. At this stage, if the parent gives her a lecture on why pushing a sibling is very bad, she may not have the capacity to listen.

So, after the parent acknowledges her, they give her some time to calm down. May be later that night, the parent can lie down next to her and state their expectations.

Parent: “Shirin, you understand that Sahil is still tiny and vulnerable.”

Shirin: “Ya, ya”

Parent: “You cannot push him or hurt him in any way. That’s just not ok”

Shirin: “Ok”

(As a parent, before you state an expectation, ensure you create capacity within a child to listen to you. If this is not done, the child may adhere to your expectation once (to avoid punishment) but might come back to the same disruptive behavior fairly soon.

Also, repeat your expectations multiple times to children whenever you get an opportunity, so that they can remember what is expected of them.)

6. Take the next steps:

In this example, the next steps would not just be for the child (i.e. no hitting, pushing the sibling) but also for her parents (to spend more time with Shirin.)

Even if what the child does is too overwhelming for you as a parent and it pushes you to the edge, it’s better that you take a time-out and process the situation before you address it with your child instead of giving your child time-out. Because time-outs are most often seen by the child as a punishment or withdrawal of love and this causes a disconnection between the parent and the child.

However, when parents consistently practice time-in, it provides a safe space for a child to express what their needs are behind their actions. If their behavior stemmed from a hurt that they carry, time-in gives the child a safe space to process it. Also, when they make a mistake, they understand that they will have an adult by their side to process the situation and take the right actions. It also doesn’t trigger panic in them in the fear of punishment. This gives the child the capacity to listen, and actually make a change in their behavior that you expect from them in a gentler way. The parent can achieve all this while maintaining a strong connection with the child which in the long run would help the parent-child relationship thrive.

(Edited by Juhi Ramaiya)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Comments