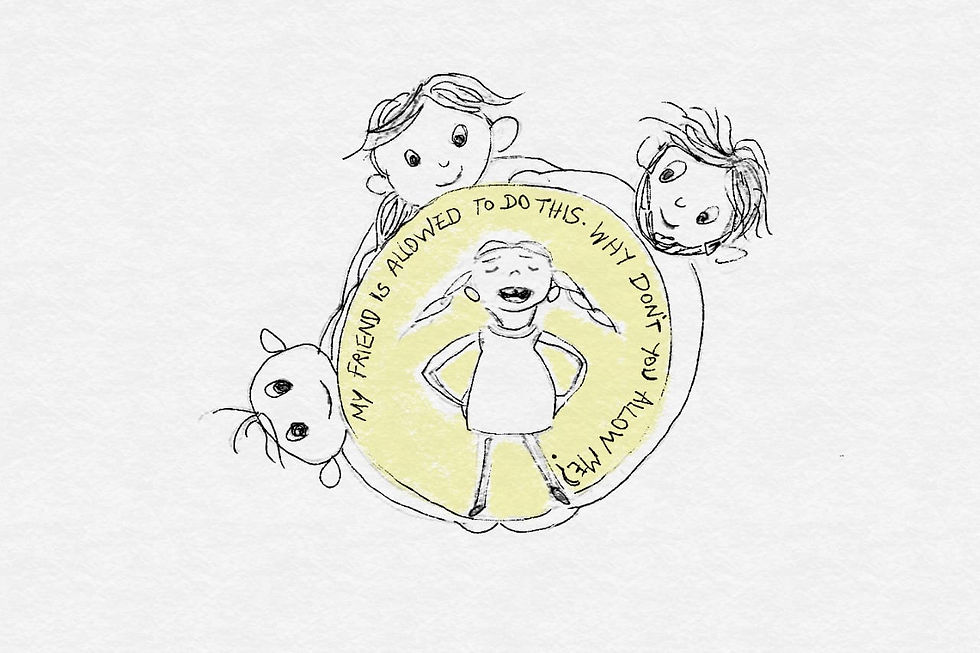

My friend is allowed to do this, why don’t you allow me?

- Growing Together

- May 13, 2020

- 6 min read

Seven-year-old Aanya wants to go for a sleepover at her friend Sia’s place. But her mother doesn’t agree to it. So Aanya asks her mother, “My friends Medha and Aishi are going for the sleepover. Why aren’t you letting me go?” Arjun, a ninth-grader, is miffed because his father tells him that he has to study regularly every day during the summer break. So Arjun asks his father, “My friends aren’t studying during the vacation. Why should I?” When children don’t get what they want, especially something that their friends have or get to do, it can give rise to such questions driven by comparison. These are quite common in a parent-child relationship. Now, as a parent, what do we do when our children compare themselves with others?

To begin with, when your child asks you a question like “My friend is allowed to do this, why don’t you allow me?”, try not to answer them in an abrupt way, saying, “Because I said so,” or “because I think it is the best for you.” Instead, give them a good, concrete explanation that will help them understand the reason behind the decision you have taken for them. A respectful reasoning will help the child understand where you are coming from. It is quite possible that your child may not agree with your decision and they may be disappointed that they are not getting what they want. However, by sharing enough information with them, you can help your child understand the reason why you are making a certain decision that could be different from others.

A younger child, say a three-year-old, is likely to accept your decision more readily and move on, but with a teenager, you are likely to face resistance. Fundamentally, as children grow older, it becomes more difficult to answer questions that arise out of comparison. However, there are certain foundational practices that you can establish, which may help you make these conversations around comparison easier, especially when children grow older.

Foundational Practice 1: Setting non-negotiables. Non-negotiables are rules that are primarily set by parents and communicated to the children. Since these are rules that you would decide on your own and only inform your child, it is a good practice to have only three to five non-negotiables and not more than that. For example, in my family, these are the non-negotiables: One, don’t be mean to others. Two, be mindful of the resources you use. And three, there will be no secrets from mama and papa, regardless of who tells you to keep something a secret. Non-negotiables typically differ from family to family, and even within a family, may change over a period of time.

Foundational Practice 2: Defining family rules. These are rules you will decide together as a family. Even children, no matter their age, should be an integral part of framing family rules. It is a good practice to sit down as a family and set family rules. These rules need not be all restrictive, they can be fun too, and can outline what to do and what not to do. You can have even 10 to 15 family rules. Remember these rules are applicable to both parents and children! Here are some examples of family rules:

1. When we sit for dinner, we will talk to each other and not look at our phones

2. We will bake a cake together once a month

3. We will not have sweets after 6 PM

4. We will play board games every Sunday

and so on.

Foundational Practice 3: Establishing family values. These are values that you believe in as a family. Children too have to be a part of deciding family values. Whenever a child is not sure if a decision is correct or not, family values act as a guidepost. When family values are set, it can help the child refer to them and see if the decision taken aligns with the values they believe in as a family. Let’s take an instance where a five-year-old is asking his mother why he can’t stay up all night. The mother, who has by now explained to her son what caring means, can tell him that one of their family values is care. She can tell him, “Caring means caring for yourself too. Sleeping is an important part of caring for yourself.” Offering this explanation based on family values can help the child understand why his mother says that he can’t stay up all night.

Foundational Practice 4: Doing regular family gratitude circles. This is a very good foundational practice through which all family members including children get to express gratitude for the family they belong to. Gratitude circles can be done once or twice a month based on your convenience. The fundamental goal of this practice is to share what you are grateful to your family for. For instance, you could say things like, “I am grateful to this family because we laugh a lot together” or “I am grateful to this family because we apologise when we hurt each other” and so on. A child could say “I am grateful to this family because my parents encourage adventure.” When a child is increasingly part of family gratitude circles, they grow more and more grateful to the family they belong to. In the long run, they will begin to understand that they get to do so many wonderful things by being a part of their family that it is ok to let go of one or two things that do not align with the beliefs and practices of their family.

The most significant advantage of establishing and following these foundational practices over a period of time is that you will have enough information to share with your child when they come to you with a question comparing themselves with someone else. When your child asks you, “My friend is getting to do this, why not me?”, you can run through your set of non-negotiables, family rules, or family values, and see if the what your child is asking for clashes with any of these. If it does, then it is easier for you to share concrete information with your child saying, “I am saying no because this goes against our family values,” or “because it’s not part of our family rules” or “because it falls under our non-negotiables.” And practicing gratitude circles will ensure that the child gets naturally tuned to some level of understanding about how things work for your family, and they are likely to compare lesser and lesser with time.

Nonetheless, it’s not that only if you follow these foundational practices will you be able to answer your child’s questions on the comparison. You can go ahead and answer their question as long as you have a strong reason to offer at that instant. Give your child enough information so that they can understand why you took a certain decision. Having said that, it is a good idea to start laying down the foundations because when you do, it becomes a lot easier for you as a parent to answer your child’s questions that are fuelled by comparison.

It is also important to remember that whenever your child does come up with such a question, first ask yourself, “Can I change my stance?” and only when you feel that you have strong reasoning to offer, take a stand and explain it to your child. If you don’t have a solid reason, be flexible to change your position on the decision.

It is also a good practice to be transparent about the decisions you take as an adult (not only those pertaining to the child). When you do so regularly, your child is likely to absorb the way you take decisions and will, over time, understand where you are coming from.

Last but not the least, keep having conversations with your child about the uniqueness of your family. When you have these discussions proactively without waiting for the child to come and ask a comparison question, the child will begin to understand that each family is unique, and comes with its own set of dynamics. They will realise that families are different and that the dynamics are different within every family – that by being a part of this family, they get to enjoy many things, and therefore it is okay to let go of few things that they don’t get to do.

By establishing the foundational steps and following them over a period of time, and by being flexible, transparent, and talking frequently about the uniqueness of your family with your child, you can enable your child to gain a rooted understanding that it all comes with being a part of the family. And eventually, this may lead to fewer instances of your child comparing themselves with others and in the long run, feeling grateful for being a part of your family.

(Edited by Anupama Krishnakumar)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Comments